Albert Speer

Hitlers Architect

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer. (19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he was convicted at the Nuremberg trial and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

An architect by training, Speer joined the Nazi Party in 1931. His architectural skills made him increasingly prominent within the Party, and he became a member of Hitler's inner circle. Hitler commissioned him to design and construct structures including the Reich Chancellery and the Nazi party rally grounds in Nuremberg. In 1937, Hitler appointed Speer as General Building Inspector for Berlin. In this capacity he was responsible for the Central Department for Resettlement that evicted Jewish tenants from their homes in Berlin. In February 1942, Speer was appointed as Reich Minister of Armaments and War Production. Using misleading statistics, he promoted himself as having performed an armaments miracle that was widely credited with keeping Germany in the war. In 1944, Speer established a task force to increase production of fighter aircraft. It became instrumental in exploiting slave labor for the benefit of the German war effort.

After the war, Albert Speer was among the 24 "major war criminals" charged with the crimes of the Nazi regime before the International Military Tribunal. He was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, principally for the use of slave labor, narrowly avoiding a death sentence. Having served his full term, Speer was released in 1966. He used his writings from the time of imprisonment as the basis for two autobiographical books, Inside the Third Reich and Spandau: The Secret Diaries. Speer's books were a success; the public was fascinated by an inside view of the Third Reich. Speer died of a stroke in 1981. Little remains of his personal architectural work.

Through his autobiographies and interviews, Speer carefully constructed an image of himself as a man who deeply regretted having failed to discover the monstrous crimes of the Third Reich. He continued to deny explicit knowledge of, and responsibility for, the Holocaust. This image dominated his historiography in the decades following the war, giving rise to the "Speer Myth": the perception of him as an apolitical technocrat responsible for revolutionizing the German war machine. The myth began to fall apart in the 1980s, when the armaments miracle was attributed to Nazi propaganda. Adam Tooze wrote in The Wages of Destruction that the idea that Speer was an apolitical technocrat was "absurd". Martin Kitchen, writing in Speer: Hitler's Architect, stated that much of the increase in Germany's arms production was actually due to systems instituted by Speer's predecessor (Fritz Todt) and furthermore that Speer was intimately involved in the "Final Solution".

In July 1932, the Speers visited Berlin to help out the Party before the Reichstag elections. While they were there his friend, Nazi Party official Karl Hanke recommended the young architect to Joseph Goebbels to help renovate the Party's Berlin headquarters. When the commission was completed, Speer returned to Mannheim and remained there as Hitler took office in January 1933.

The organizers of the 1933 Nuremberg Rally asked Speer to submit designs for the rally, bringing him into contact with Hitler for the first time. Neither the organizers nor Rudolf Hess were willing to decide whether to approve the plans, and Hess sent Speer to Hitler's Munich apartment to seek his approval. This work won Speer his first national post, as Nazi Party "Commissioner for the Artistic and Technical Presentation of Party Rallies and Demonstrations".

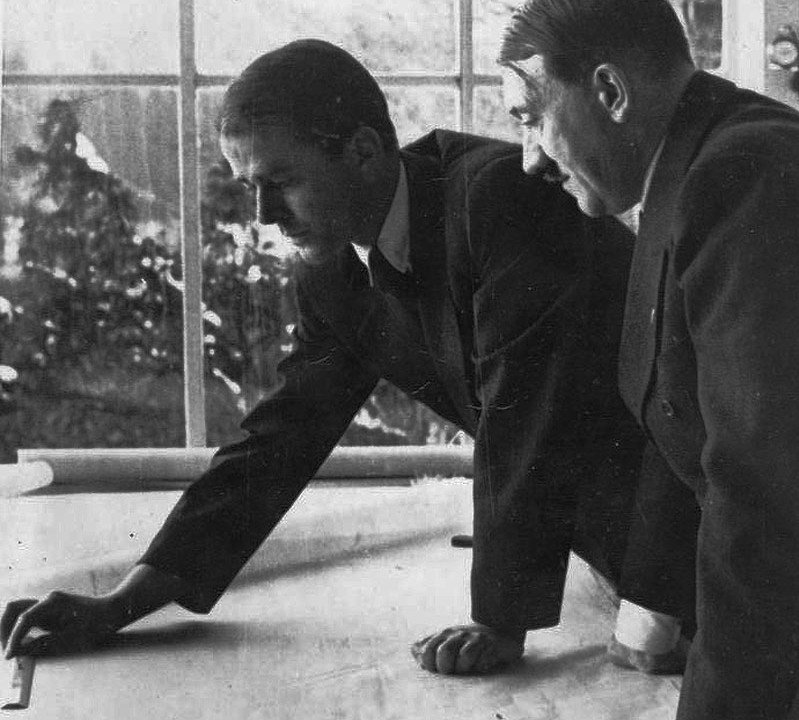

Shortly after Hitler came into power, he began to make plans to rebuild the chancellery. At the end of 1933, he contracted Paul Troost to renovate the entire building. Hitler appointed Speer, whose work for Goebbels had impressed him, to manage the building site for Troost. As Chancellor, Hitler had a residence in the building and came by every day to be briefed by Speer and the building supervisor on the progress of the renovations. After one of these briefings, Hitler invited Speer to lunch, to the architect's great excitement. Speer quickly became part of Hitler's inner circle; he was expected to call on him in the morning for a walk or chat, to provide consultation on architectural matters, and to discuss Hitler's ideas. Most days he was invited to dinner.

The New Reich Chancellory

When Troost died on 21 January 1934, Speer effectively replaced him as the Party's chief architect. Hitler appointed Speer as head of the Chief Office for Construction, which placed him nominally on Hess's staff.

One of Speer's first commissions after Troost's death was the Zeppelinfeld stadium in Nuremberg. It was used for Nazi propaganda rallies and can be seen in Leni Riefenstahl's propaganda film Triumph of the Will. The building was able to hold 340,000 people. Speer insisted that as many events as possible be held at night, both to give greater prominence to his lighting effects and to hide the overweight Nazis. Nuremberg was the site of many official Nazi buildings. Many more buildings were planned. If built, the German Stadium would have accommodated 400,000 spectators. Speer modified Werner March's design for the Olympic Stadium being built for the 1936 Summer Olympics. He added a stone exterior that pleased Hitler. Speer designed the German Pavilion for the 1937 international exposition in Paris.

Nazi Rally, Nuremburg. “ The catherdral of light”

German Pavilion for 1937 Paris expo and the Berlin stadium

On 30 January 1937, Hitler appointed Speer as General Building Inspector for the Reich Capital whivh was going to be rnamed - “Germania”. This carried with it the rank of State Secretary in the Reich government and gave him extraordinary powers over the Berlin city government. He was to report directly to Hitler, and was independent of both the mayor and the Gauleiter of Berlin. Hitler ordered Speer to develop plans to rebuild Berlin. These centered on a three-mile-long grand boulevard running from north to south, which Speer called the Prachtstrasse, or Street of Magnificence; he also referred to it as the "North–South Axis". At the northern end of the boulevard, Speer planned to build the Volkshalle, a huge domed assembly hall over 700 feet (210 m) high, with floor space for 180,000 people. At the southern end of the avenue, a great triumphal arch, almost 400 feet (120 m) high and able to fit the Arc de Triomphe inside its opening, was planned. The existing Berlin railroad termini were to be dismantled, and two large new stations built. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 led to the postponement, and later the abandonment, of these plans

More power

As one of the younger and more ambitious men in Hitler's inner circle, Speer was approaching the height of his power. In 1938, Prussian Minister President Hermann Göring had appointed him to the Prussian State Council. In 1941, he was elected to the Reichstag from electoral constituency 2 (Berlin–West). On 8 February 1942, Reich Minister of Armaments and Munitions. Fritz Todt died in a plane crash shortly after taking off from Hitler's eastern headquarters at Rastenburg. Speer arrived there the previous evening and accepted Todt's offer to fly with him to Berlin. Speer cancelled some hours before take-off because the previous night he had been up late in a meeting with Hitler. Hitler appointed Speer in Todt's place. Martin Kitchen, a British historian, says that the choice was not surprising. Speer was loyal to Hitler, and his experience building prisoner of war camps and other structures for the military qualified him for the job.[58] Speer succeeded Todt not only as Reich Minister but in all his other powerful positions, including Inspector General of German Roadways, Inspector General for Water and Energy and Head of the Nazi Party's Office of Technology. At the same time, Hitler also appointed Speer as head of the Organisation Todt, a massive, government-controlled construction company.

As Minister of Armaments, Speer was responsible for supplying weapons to the army. With Hitler's full agreement, he decided to prioritize tank production, and he was given unrivaled power to ensure success. Hitler was closely involved with the design of the tanks, but kept changing his mind about the specifications. This delayed the program, and Speer was unable to remedy the situation. In consequence, despite tank production having the highest priority, relatively little of the armaments budget was spent on it. This led to a significant German Army failure at the Battle of Prokhorovka, a major turning point on the Eastern Front against the Soviet Red Army.

As head of Organisation Todt, Speer was directly involved in the construction and alteration of concentration camps. He agreed to expand Auschwitz and some other camps, allocating 13.7 million Reichsmarks for the work to be carried out. This allowed an extra 300 huts to be built at Auschwitz, increasing the total human capacity to 132,000. Included in the building works was material to build gas chambers, crematoria and morgues. The SS called this "Professor Speer's Special Programme".

Speer realized that with six million workers drafted into the armed forces, there was a labor shortage in the war economy, and not enough workers for his factories. In response, Hitler appointed Fritz Sauckel as a "manpower dictator" to obtain new workers. Speer and Sauckel cooperated closely to meet Speer's labor demands. Hitler gave Sauckel a free hand to obtain labor, something that delighted Speer, who had requested 1,000,000 "voluntary" laborers to meet the need for armament workers. Sauckel had whole villages in France, Holland and Belgium forcibly rounded up and shipped to Speer's factories. Sauckel obtained new workers often using the most brutal methods. In occupied areas of the Soviet Union, that had been subject to partisan action, civilian men and women were rounded up en masse and sent to work forcibly in Germany. By April 1943, Sauckel had supplied 1,568,801 "voluntary" laborers, forced laborers, prisoners of war and concentration camp prisoners to Speer for use in his armaments factories. It was for the maltreatment of these people, that Speer was principally convicted at the Nuremberg Trials.

Speer as head of Organisation Todt.

By April 1945, little was left of the armaments industry, and Speer had few official duties. Speer visited the Führerbunker on 22 April for the last time. He met Hitler and toured the damaged Chancellery before leaving Berlin to return to Hamburg. On 29 April, the day before committing suicide, Hitler dictated a final political testament which dropped Speer from the successor government. Speer was to be replaced by his subordinate, Karl-Otto Saur. Speer was disappointed that Hitler had not selected him as his successor. After Hitler's death, Speer offered his services to the so-called Flensburg Government, headed by Hitler's successor, Karl Dönitz. He took a role in that short-lived regime as Minister of Industry and Production. Speer provided information to the Allies, regarding the effects of the air war, and on a broad range of subjects, beginning on 10 May. On 23 May, two weeks after the surrender of German forces, British troops arrested the members of the Flensburg Government and brought Nazi Germany to a formal end

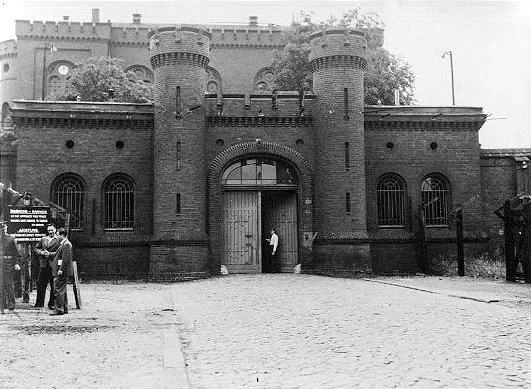

On 18 July 1947, Speer was transferred to Spandau Prison in Berlin to serve his prison term. There he was known as Prisoner Number Five. Speer's parents died while he was incarcerated. His father, who died in 1947, despised the Nazis and was silent upon meeting Hitler. His mother died in 1952. As a Nazi Party member, she had greatly enjoyed dining with Hitler.

Speer in Flensburg, The end of Nazi Germany

Speer at the Nuremburg Trials

Speer was taken to several internment centres for Nazi officials and interrogated. In September 1945, he was told that he would be tried for war crimes, and several days later, he was moved to Nuremberg and incarcerated there. Speer was found guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity, principally for the use of slave labor and forced labor. He was acquitted on the other two counts. He had claimed that he was unaware of Nazi extermination plans, and the Allies had no proof that he was aware. His claim was revealed to be false in a private correspondence written in 1971 and publicly disclosed in 2007. On 1 October 1946, he was sentenced to 20 years' imprisonment. While three of the eight judges (two Soviet and American Francis Biddle) advocated the death penalty for Speer, the other judges did not, and a compromise sentence was reached after two days of discussions

Much of Speer's energy was dedicated to keeping fit, both physically and mentally, during his long confinement. Spandau had a large enclosed yard where inmates were allocated plots of land for gardening. Speer created an elaborate garden complete with lawns, flower beds, shrubbery, and fruit trees. To make his daily walks around the garden more engaging Speer embarked on an imaginary trip around the globe. Carefully measuring distance travelled each day, he mapped distances to the real-world geography. He had walked more than 30,000 kilometres (19,000 mi), ending his sentence near Guadalajara, Mexico. Speer also read, studied architectural journals, and brushed up on English and French. In his writings, Speer claimed to have finished five thousand books while in prison. His sentence of twenty years amounted to 7,305 days, which only allotted one and a half days per book

Speer's release from prison was a worldwide media event. Reporters and photographers crowded both the street outside Spandau and the lobby of the Hotel Berlin where Speer spent the night. He said little, reserving most comments for a major interview published in Der Spiegel in November 1966. Although he stated he hoped to resume an architectural career, his sole project, a collaboration for a brewery, was unsuccessful. Instead, he revised his Spandau writings into two autobiographical books, Inside the Third Reich and Spandau: The Secret Diaries. Speer made himself widely available to historians and other enquirers. In October 1973, he made his first trip to Britain, flying to London to be interviewed on the BBC Midweek programme. In the same year, he appeared on the television programme The World at War. Speer returned to London in 1981 to participate in the BBC Newsnight programme. He suffered a stroke and died in London on 1 September.

He had remained married to his wife, but he had formed a relationship with a German woman living in London and was with her at the time of his death. His daughter, Margret Nissen, wrote in her 2005 memoirs that after his release from Spandau he spent all of his time constructing the "Speer Myth".

Speer maintained at the Nuremberg trials and in his memoirs that he had no direct knowledge of the Holocaust. He admitted only to being uncomfortable around Jews in the published version of the Spandau Diaries. In his final statement at Nuremberg, Speer gave the impression of apologizing, although he did not directly admit any personal guilt and the only victim he mentioned was the German people. Historian Martin Kitchen states that Speer was actually "fully aware of what had happened to the Jews" and was "intimately involved in the 'Final Solution'"

In 2005, The Daily Telegraph reported that documents had surfaced indicating that Speer had approved the allocation of materials for the expansion of Auschwitz concentration camp after two of his assistants inspected the facility on a day when almost a thousand Jews were massacred. Heinrich Breloer, discussing the construction of Auschwitz, said Speer was not just a cog in the works—he was the "terror itself"

Speer buried with his family in Heidelberg.

Born

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer

19th March 1905

Mannheim, Grand Duchy of Baden, German Empire

Died

1st September 1981 (aged 76)

St Mary's Hospital, London, England