The Bürgerbräukeller Bomb

08.11.1939

The Bürgerbräukeller (brew cellar) was a large beer hall in Munich, Germany. Opened in 1885, it was one of the largest beer halls of the Bürgerliches Brauhaus. After Bürgerliches merged with Löwenbräu in 1921, the hall was transferred to that company.

The Bürgerbräukeller was where Adolf Hitler launched the Beer Hall Putsch in November 1923 and where he announced the re-establishment of the Nazi Party in February 1925. In 1939, the beer hall was the site of an attempted assassination of Hitler and other Nazi leaders by Georg Elser. It survived aerial bombing in World War II.

The Bürgerbräukeller was demolished in 1979 and the Gasteig complex (Offices, Library and Concert venue) was built on its site.

A meeting of the Nazi Party at the Bürgerbräukeller beer hall, circa 1923

From 1920 to 1923, the Bürgerbräukeller was one of the main gathering places of the Nazi Party. There, on 8 November 1923, Adolf Hitler launched the Beer Hall Putsch. After Hitler seized power in 1933, he commemorated each anniversary on the night of 8 November with an address to the Alte Kämpfer (Old Fighters) in the great hall of the Bürgerbräukeller. The following day, a re-enactment was conducted of the march through the streets of Munich from the Bürgerbräukeller to Königsplatz. The event climaxed with a ceremony at the Feldherrnhalle to revere the 16 'blood martyrs' of the Beer Hall Putsch.

The Bürgerbräukeller was also the site Hitler chose to publicly announce the re-establishment of the Nazi Party on 27 February 1925, some ten weeks after his release from Landsberg prison. With a sense of theater and symbolism, he returned in triumph to the scene of his failed putsch of sixteen months earlier. Three hours before his 8:00 p.m. speech, the hall was filled to capacity with 3,000 attendees and 2,000 more were turned away. Hitler spoke for two hours and reclaimed leadership of the Nazi movement, unifying the feuding factions that had led the fragmented organization while he was incarcerated.

Invitation to a "re-establishment" of the Nazi party with Adolf Hitler as an orator, 27 February 1925, Munich, Bürgerbräukeller

As early as the 16th century, brewers in Bavaria would collect the barrels of beer near the end of the brewing season and stock them in specially developed cellars for the summer. By the 18th century, brewers discovered they could make a greater profit if they opened their garden-topped cellars to the public and served the beer on site. In the 20th century, the Bürgerbräukeller had both a cellar and a beer garden, as well as the grand hall for indoor functions.

The grand hall was a rectangular space accommodating up to 3,000 people, though less in full dining mode. Freestanding pillars on either side of the hall supported narrow galleries and the roof. The load-bearing walls and the internal pillars with classical capitals were plastered brickwork. A decorative plastered ceiling, divided into bays with three rows of chandeliers, concealed steel beams supporting the timber roof structure.

The Man

Johann Georg Elser (4 January 1903 – 9 April 1945) was a German worker who planned and carried out an elaborate assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler and other high-ranking Nazi leaders on 8 November 1939 at the Bürgerbräukeller in Munich (known as the Bürgerbräukeller Bombing). Elser constructed and placed a bomb near the platform from which Hitler was to deliver a speech. It did not kill Hitler, who left earlier than expected, but it did kill 8 people and injured 62 others. Elser was held as a prisoner for more than five years until he was executed at Dachau concentration camp less than a month before the surrender of Nazi Germany.

Hitler giving his speech 08.11.1939

Ideology and religion

Elser, a carpenter and cabinet-maker by trade, became a member of the left-leaning Federation of Woodworkers Union. He also joined the Red Front-Fighters' Association, although he told his interrogators in 1939 that he attended a political assembly no more than three times while a member. He also stated that he voted for the Communist Party until 1933, as he considered the KPD the best defender of workers' interests. There is evidence that Elser opposed Nazism from the beginning of the regime in 1933; he refused to perform the Hitler salute, did not join others in listening to Hitler's speeches broadcast on the radio, and did not vote in the elections or referendums during the Nazi era.

Elser met Josef Schurr, a Communist from Schnaitheim, at a Woodworkers' Union meeting in Königsbronn in 1933. Elser had extreme views, supported by a letter that Schurr sent to a newspaper in Ulm in 1947 which stated that Elser "was always extremely interested in some act of violence against Hitler and his cronies. He always called Hitler a 'gypsy'—one just had to look at his criminal face."

Elser's parents were Protestant, and he attended church with his mother as a child, though his attendance lapsed. His church attendance increased during 1939 - after he had decided to carry out the assassination attempt - either at a Protestant or Roman Catholic church. He claimed that church attendance and the recitation of the Lord's Prayer calmed him. He told his arresting officers: "I believe in the survival of the soul after death, and I also believed that I would not go to heaven if I had not had an opportunity to prove that I wanted good. I also wanted to prevent by my act even greater bloodshed."

Johann Georg Elser

The Motive

During four days of interrogation in Berlin (19–22 November 1939), Elser articulated his motive to his interrogators:

I considered how to improve the conditions of the workers and avoid a war. For this I was not encouraged by anyone ... Even from Radio Moscow I never heard that the German government and the regime must be overthrown. I reasoned the situation in Germany could only be modified by a removal of the current leadership, I mean Hitler, Goering and Goebbels ... I did not want to eliminate Nazism ... I was merely of the opinion that a moderation in the policy objectives will occur through the elimination of these three men ... The idea of eliminating the leadership came to me in the fall of 1938 ... I thought to myself that this is only possible if the leadership is together at a rally. From the daily press I gathered that the next meeting of leaders was happening on 8 and 9 November 1938 in Munich in the Bürgerbräukeller.

Five years later in Dachau concentration camp, SS officer Lechner claimed Elser revealed his motive to him:

I had to do it because, for his whole life, Hitler has meant the downfall of Germany ... don't think that I'm some kind of dyed-in-the-wool Communist — I'm not. I have some sympathy for Ernst Thälmann, but getting rid of Hitler just became an obsession of mine ... But, as you can see — I got caught, and now I have to pay for it. I would have preferred it if they executed me right away.

The Plan

In order to find out how best to implement his assassination plan, Elser travelled to Munich by train on 8 November 1938, the day of Hitler's annual speech on the anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch. Elser was not able to enter the Bürgerbräukeller until 10:30 p.m., when the crowd had dispersed. He stayed until midnight before going back to his lodging. The next morning, he returned to Königsbronn. On the following day, 10 November, the anti-Jewish violence of the Kristallnacht took place in Munich. "In the following weeks I slowly concocted in my mind that it was best to pack explosives in the pillar directly behind the speaker's podium," Elser told his interrogators a year later. He continued to work in the Waldenmaier armament factory in Heidenheim and systematically stole explosives, hiding packets of powder in his bedroom. Realising he needed the exact dimensions of the column to build his bomb he returned to Munich, staying 4–12 April 1939. He took a camera with him, a Christmas gift from Maria Schmauder (Daughter of the family he lived with). He had just become unemployed due to an argument with a factory supervisor.

In April–May 1939, Elser found a labouring job at the Vollmer quarry in Königsbronn. While there, he collected an arsenal of 105 blasting cartridges and 125 detonators, causing him to admit to his interrogators, "I knew two or three detonators were sufficient for my purposes, but I thought the surplus will increase the explosive effect." Living with the Schmauder family in Schnaitheim he made many sketches, telling his hosts he was working on an "invention".

In July, in a secluded orchard owned by his parents, Elser tested several prototypes of his bomb. Clock movements given to him in lieu of wages when leaving Rothmund in Meersburg in 1932 and a car indicator "winker" were incorporated into the "infernal machine". In August, after a bout of sickness, he left for Munich. Powder, explosives, a battery and detonators filled the false bottom of his wooden suitcase. Other boxes contained his clothes, clock movements and the tools of his trade.

The Bürgerbräukeller

Elser arrived in Munich on 5 August 1939. Using his real name, he rented a room in the apartments of two unsuspecting couples, at first staying with the Baumanns and from 1 September, Alfons and Rosa Lehmann. He soon became a regular at the Bürgerbräukeller restaurant for his evening meal. As before, he was able to enter the adjoining Bürgerbräukeller Hall before the doors were locked at about 10:30 p.m.

Over the next two months, Elser stayed all night inside the Bürgerbräukeller 30 to 35 times. Working on the gallery level and using a flashlight dimmed with a blue handkerchief, he started by installing a secret door in the timber panelling to a pillar behind the speaker's rostrum. After removing the plaster behind the door, he hollowed out a chamber in the brickwork for his bomb. Normally completing his work around 2:00–3:00 a.m., he dozed in the storeroom off the gallery until the doors were unlocked at about 6:30 a.m. He then left via a rear door, often carrying a small suitcase filled with debris.

Security was relatively lax at the Bürgerbräukeller. Christian Weber, a veteran from the Beer Hall Putsch and the Munich city councillor, was responsible. However, from the beginning of September, after the outbreak of war with Poland, Elser was aware of the presence of air raid wardens and two "free-running dogs" in the building.

While he worked at night in the Bürgerbräukeller, Elser built his device during the day. He purchased extra parts, including sound insulation, from local hardware stores and became friends with the local master woodworker, Brög, who allowed him use of his workshop.

On the nights of 1–2 November, Elser installed the explosives in the pillar. On 4–5 November, which were Saturday and Sunday dance nights, he had to buy a ticket and wait in the gallery until after 1 a.m. before he could install the twin-clock mechanism that would trigger the detonator. To celebrate the completion of his work, Elser recalled later, "I left by the back road and went to the Isartorplatz where at the kiosk I drank two cups of coffee."

On 6 November, Elser left Munich for Stuttgart to stay overnight with his sister, Maria Hirth, and her husband. Leaving them his tool boxes and baggage, he returned to Munich the next day for a final check. Arriving at the Bürgerbräukeller at 10 p.m., he waited for an opportunity to open the bomb chamber and satisfy himself the clock mechanism was correctly set. The next morning he departed Munich by train for Friedrichshafen via Ulm. After a shave at a hairdresser, he took the 6:30 p.m. steamer to Konstanz.

Hitler's escape

The high-ranking Nazis who accompanied Adolf Hitler to the anniversary of the Beer Hall Putsch on 8 November 1939 were Joseph Goebbels, Reinhard Heydrich, Rudolf Hess, Robert Ley, Alfred Rosenberg, Julius Streicher, August Frank, Hermann Esser and Heinrich Himmler. Hitler was welcomed to the platform by Christian Weber.

Unknown to Elser, Hitler had initially cancelled his speech at the Bürgerbräukeller to devote his attention to planning the imminent war with France, but changed his mind and attended after all. As fog was forecast, possibly preventing him from flying back to Berlin the next morning, Hitler decided to return to Berlin the same night by his private train. With the departure from Munich's main station set for 9:30 p.m., the start time of the reunion was brought forward half an hour to 8 p.m. and Hitler cut his speech from the planned two hours to a one-hour duration.

Hitler ended his address to the 3000-strong audience of the party faithful at 9:07 p.m., 13 minutes before Elser's bomb exploded at 9:20 p.m. By that time, Hitler and his entourage had left the Bürgerbräukeller. The bomb brought down part of the ceiling and roof and caused the gallery and an external wall to collapse, leaving a mountain of rubble. About 120 people were still in the hall at the time. Seven were killed (the cashier Maria Henle, Franz Lutz, Wilhem Kaiser, a radio announcer named Weber, Leonhard Reindl, Emil Kasberger, and Eugen Schachta). Another sixty-three were injured, sixteen seriously, with one dying later. All but one of those killed were members of the Nazi Party, of which all but one had been longtime supporters of the ideology.

Hitler did not learn of the attempt on his life until later that night on a stop in Nuremberg. When told of the bombing by Goebbels, Hitler responded, "A man has to be lucky." A little later Hitler had a different spin, saying, "Now I am completely at peace! My leaving the Bürgerbräukeller earlier than usual is proof to me that Providence wants me to reach my goal."

Aftermath of the Bomb

Arrest

At 8:45 p.m. on the night of 8 November, Elser was apprehended by two border guards, 25 metres (80 ft) from the Swiss border fence in Konstanz. When taken to the border control post and asked to empty his pockets he was found to be carrying wire cutters, numerous notes and sketches pertaining to explosive devices, firing pins and a blank colour postcard of the interior of the Bürgerbräukeller. At 11 p.m., during Elser's interrogation by the Gestapo in Konstanz, news of the bombing in Munich arrived by teleprinter. The next day, Elser was transferred by car to Munich Gestapo Headquarters.

Investigation

While still returning to Berlin by train, Hitler ordered Heinrich Himmler to put Arthur Nebe, head of Kripo (Criminal Police), in charge of the investigation into the Munich bombing. Himmler did this, but also assigned total control of the investigation to the chief of the Gestapo, Heinrich Müller. Müller immediately ordered the arrest of all Bürgerbräukeller personnel, while Nebe ran the onsite investigation, sifting through the debris.

Nebe had early success, finding the remains of brass plates bearing patent numbers of a clock maker in Schwenningen, Baden-Würtemberg. Despite the clear evidence of the German make, Himmler released to the press that the metal parts pointed to "foreign origin".

Himmler offered a reward of 500,000 marks for information leading to the capture of the culprits, and the Gestapo was soon deluged with hundreds of suspects. When one suspect was reported to have detonator parts in his pockets, Otto Rappold of the counter-espionage arm of the Gestapo sped to Königsbronn and neighbouring towns. Every family member and possible acquaintance of Elser was rounded up for interrogation.

At the Schmauder residence in Schnaitheim, 16-year-old Maria Schmauder told of her family's recent boarder who was working on an "invention", had a false bottom in his suitcase, and worked at the Vollmer quarry.

Imprisonment

Elser never faced a trial for the bombing of the Bürgerbräukeller. After his year of torment at Berlin Gestapo Headquarters, he was kept in special custody in Sachsenhausen concentration camp between early 1941 and early 1945. At Sachsenhausen, Elser was held in isolation in a T-shaped building reserved for protected prisoners. Accommodated in three joined cells, each 9.35 m2, there was space for his two full-time guards and a work space to make furniture and other things, including several zithers (musical instruments).

Elser's apparent preferential treatment, which included extra rations and daily visits to the camp barber for a shave, aroused interest amongst other prisoners, including British SIS officer Payne Best. He wrote later that Elser was also allowed regular visits to the camp brothel. Martin Niemöller was also a special inmate in the Sachsenhausen "bunker" and believed the rumours that Elser was an SS man and an agent of Hitler and Himmler. Elser kept a photo of Elsa Härlen in his cell. In early 1945, Elser was transferred to the bunker at Dachau concentration camp.

Death

In April 1945, with German defeat imminent, the Nazis' intention of staging a show trial over the Bürgerbräukeller bombing had become futile. Hitler ordered the execution of special security prisoner "Eller" — the name used for Elser in Dachau — along with Wilhelm Canaris, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and others who had plotted against him. The order, dated 5 April 1945, from the Gestapo HQ in Berlin, was addressed to the Commandant of the Dachau concentration camp, SS-Obersturmbannführer Eduard Weiter.

On 9 April 1945, four weeks before the end of the war in Europe, Georg Elser was shot dead and his fully dressed body immediately burned in the crematorium of Dachau Concentration Camp. He was 42 years old.

Remembering Elser

There are at least 60 streets and places named after Elser in Germany and several monuments.

Claus Christian Malzahn wrote in 2005: 'That he was for so long ignored by the historians of both East and West Germany, merely goes to show just how long it took Germany to become comfortable with honestly confronting its own history. Johann Georg Elser, though, defied ideological categorization—and for that reason, he is a true German hero.

Memorials to Elser in Berlin

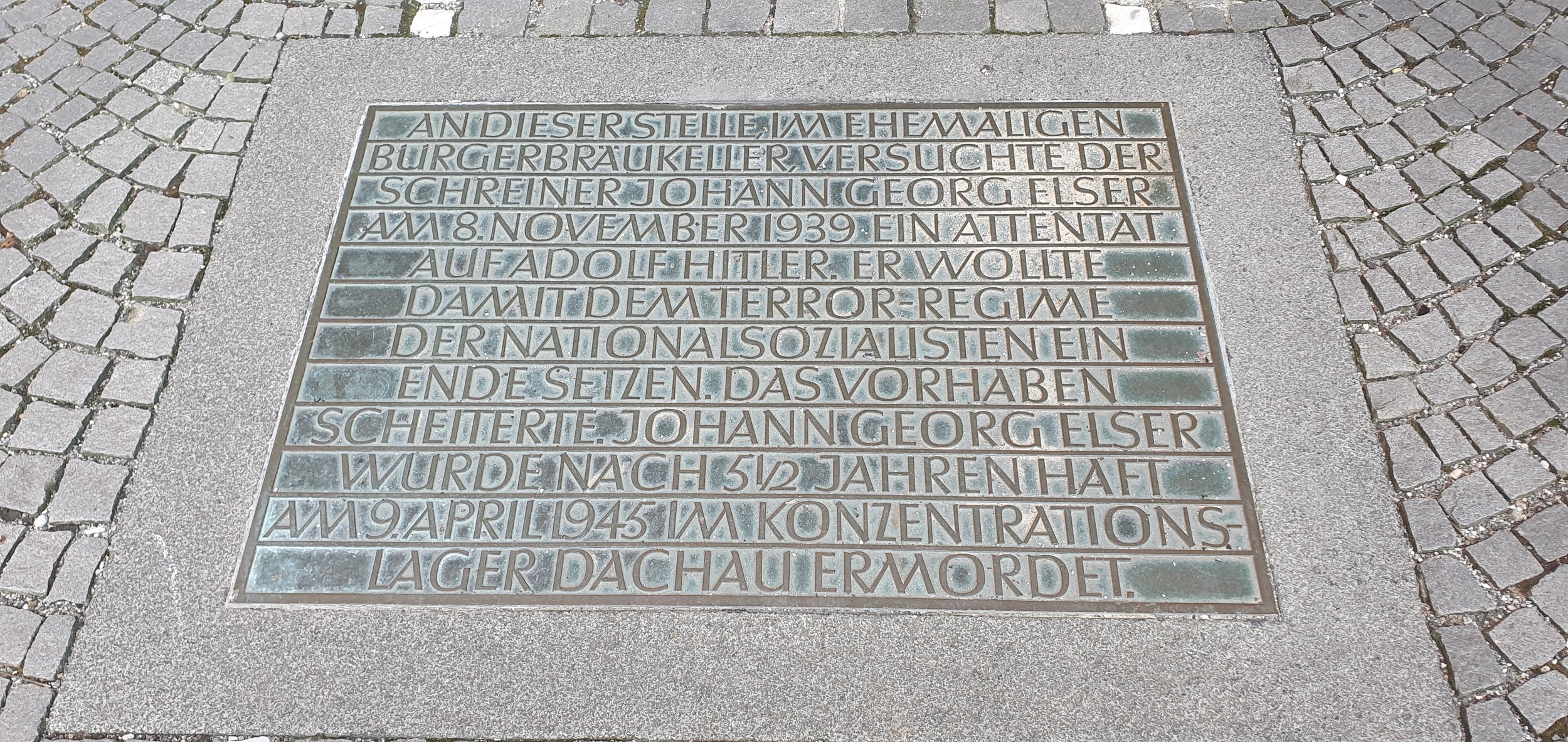

My Photos of the Burgerbraukeller area now, Elser’s Plaque in Munich and the Memorial in Berlin

Watch the trailer for the 2017 German movie of the Burgerbraukeller Bomb plot.